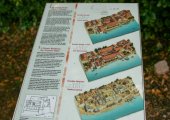

Butrint, located in the south of Albania approximately 15 km from the modern city of Saranda, has a special atmosphere created by a combination of archaeology, monuments and nature in the Mediterranean. With its hinterland it constitutes an exceptional cultural landscape, which has developed organically over many centuries. Butrint has escaped aggressive development of the type that has reduced the heritage value of most historic landscapes in the Mediterranean region. It constitutes a very rare combination of archaeology and nature. The property is a microcosm of Mediterranean history, with occupation dating from 50, 000 BC, at its earliest evidence, up to the 19th century AD. Prehistoric sites have been identified within the nucleus of Butrint, the small hill surrounded by the waters of Lake Butrint and Vivari Channel, as well as in its wider territory. From 800 BC until the arrival of the Romans, Butrint was influenced by Greek culture, bearing elements of a “polis” and being settled by Chaonian tribes. In 44 BC Butrint became a Roman colony and expanded considerably on reclaimed marshland, primarily to the south across the Vivari Channel, where an aqueduct was built. In the 5th century AD Butrint became an Episcopal centre; it was fortified and substantial early Christian structures were built. After a period of abandonment, Butrint was reconstructed under Byzantine control in the 9th century. Butrint and its territory came under Angevin and then Venetian control in the 14th century. Several attacks by despots of Epirus and then later by Ottomans led to the strengthening and extension of the defensive works of Butrint. At the beginning of the 19th century, a new fortress was added to the defensive system of Butrint at the mouth of the Vivari Channel. It was built by Ali Pasha, an Albanian Ottoman ruler who controlled Butrint and the area until its final abandonment.

The fortifications bear testimony to the different stages of their construction from the time of the Greek colony until the Middle Ages. The most interesting ancient Greek monument is the theatre which is fairly well preserved. The major ruin from the paleo-Christian era is the baptistery, an ancient Roman monument adapted to the cultural needs of Christianity. Its floor has a beautiful mosaic decoration. The paleo-Christian basilica was rebuilt in the 9th century and the ruins are sufficiently well preserved to permit analysis of the structure (three naves with a transept and an exterior polygonal apse).

The evolution of the natural environment of Butrint led to the abandonment of the city at the end of the Middle Ages, with the result that this archaeological site provides valuable evidence of ancient and medieval civilizations on the territory of modern Albania.

The property is of sufficient size (200 ha) to include a significant proportion of the attributes which express its Outstanding Universal Value. The buried archaeological sites, standing ruins and historic buildings are sufficiently intact. While the World Heritage property Butrint does not suffer significantly from adverse effects of development or neglect, there are vulnerabilities, such as increases in seasonal water levels, the need for better coordination of conservation works and archaeological excavations, vegetation growth, and structural instability of some monuments. There are also some pressures from modern development, including roads and urban expansion around the property. Nonetheless, Butrint still is an excellent case of preservation of ancient and medieval urban occupation. The surrounding landscape provides the context for the past urban change at Butrint.

The authenticity of the World Heritage property Butrint is related to its excellent preservation on a site where the changing human interaction with the environment can be observed in the surviving monuments, the below-ground archaeology and the surrounding landscape. The quality of the restoration and conservation work carried out since 1924 has been high. Later interventions have abided by contemporary standards as set out in the 1964 Venice Charter.

Butrint National Park was inscribed on the National Heritage List of Protected Monuments in 1948. Currently, the protection and conservation of the archeological monuments is covered by the Law on Cultural Heritage. The natural values of the Butrint Wetlands were recognized by the Ramsar Convention in 2002. In 2005, based on the Law on Protected Areas, Butrint was declared a National Park covering 86 km². The National Park acts as a buffer zone for the World Heritage property. The National Park, which has a Board chaired by the Minister of Culture and professional staff, is responsible for the management of the World Heritage property. The national Institute of Cultural Monuments and the Institute of Archaeology are responsible for all research, excavations and consolidation of architectural and archaeological remains.

Butrint manifests several vulnerable aspects. Potentially these vulnerabilities could threaten the integrity of the property in the long term. To avoid threats to integrity and authenticity, monitoring and controlling the vulnerabilities are crucial issues in the Management Plan of Butrint on Archaeology and Monuments. The Management Plan must be harmonized with other plans covering the property and the National Park.

Source: unesco.org